Conservation incentives are a win-win

Providing incentives to reduce hunting wild animals for meat can benefit people and wildlife. Born Free’s Head of Conservation Dr Nikki Tagg reports on exciting new research from the Dja Biosphere Reserve, Cameroon.

Chimpanzee in a tree

A three-year research project in the Dja Biosphere Reserve in Cameroon has reported success in changing local hunter behaviour and reducing ‘bushmeat’ hunting (the hunting of wild animals for their meat). The encouraging project includes the signing of environmental agreements, whereby bushmeat hunters commit to reducing hunting, and in return receive economic incentives. Hunters who signed an agreement, participated in alternative income schemes to generate a reliable and sustainable income, helping bushmeat hunters to transition away from unsustainable hunting. The findings of the project support the approach of Born Free’s Guardians of Dja programme – incentivising conservation by supporting skills training for sustainable trades, such as cocoa farming.

Around the Dja, bushmeat hunting is a common practice that can be catastrophic for slow-reproducing, relatively rare, threatened animals, like chimpanzees, gorillas, and forest elephants. As hunters are key actors in the fate of such species, it is crucial to understand what can influence their hunting behaviour.

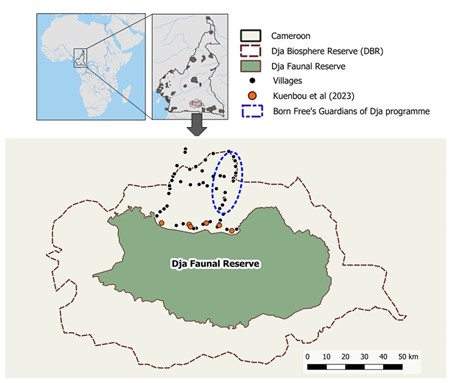

The project – a collaboration between a number of local partners, that ran between 2018 and 2021 – provided support to rural communities living in the buffer zone of the Dja Biosphere Reserve to develop cocoa farming and fishing practices, the two main economic activities, aside from bushmeat hunting, traditionally practiced in the area. The project provided technical support, materials, and access to markets to enable local people/community members engaged in the project to generate a reliable and sustainable income, without the need to engage in bushmeat hunting.

A total of 64 farmers were involved in the study: 35 of them signed ‘reciprocal environmental agreements’ at the start of the project, pledging to reduce their engagement in bushmeat hunting in return for their participation in the alternative livelihoods scheme. Data were collected on bushmeat offtake (for example, which species were being hunted and the weight of meat) and hunters self-reported information such as time spent hunting in the forest and their financial situation. After 15 months of project activities, each farmer was interviewed again.

A map showing the location of villages on the periphery of the Dja Faunal Reserve included in the study, as well as the location of the Guardians of Dja programme.

It was noted that all farmers caught similar amounts of bushmeat at the start of the study. Over the course of the project, hunters who had signed the environmental agreements and participated in the alternative livelihood scheme spent more time working on their farms and were therefore able to increase their income from cocoa farming by 47%. Overall, less time was spent hunting, particularly with guns. This reduction in gun hunting is of huge importance, because this method of hunting is often used to target larger bodied species, including highly threatened primates.

There was no decline in the number of traps set in the forest surrounding the villages, likely to be because trapping takes less time and money that many, if not most, people engage in it to provide protein in their diets. This is supported by the observation that those who signed environmental agreements sold less bushmeat, instead eating a larger proportion of what they caught in their snares in the forest.

The study’s lead author, Cameroonian PhD student Jacques Kuenbou, explains that “the results are exciting because they offer hope that positive change is achievable”. The economic incentives provided to certain groups of individuals through reciprocal environment agreements can promote livelihood paradigm shifts, alleviating poverty, and decreasing dependence on natural resources. In short, says Jacques: “By incentivizing responsible hunting practices, we achieve a win-win situation: hunters benefit from incentives, and wildlife populations are safeguarded.”

Born Free’s Dr Nikki Tagg, who was involved in the study, is very encouraged by the findings, explaining that “with the right choices and opportunities, people living alongside the wildlife of the Dja can move away from a reliance on commercial hunting, and are able to thrive while allowing wildlife to do the same. In this way, people can truly become the Guardians of Dja.”

The project demonstrates the importance of ‘incentive-based conservation’ to encourage positive behavioural changes in a win-win situation, benefitting people and wildlife alike. Born Free’s Guardians of Dja programme aims to achieve the same for the people and wildlife in the region, also encouraging hunters to sign reciprocal environmental agreements in return for participation in alternative livelihood schemes. As a holistic programme, Guardians of Dja also provides education and community outreach, support for wildlife law enforcement and sensitisation in the community, and forest protection and restoration activities, providing benefits to people as well as great apes, pangolins, forest elephants, and a host of other wildlife species.

With your continued support, we hope to be reporting similar stories of success in the future!